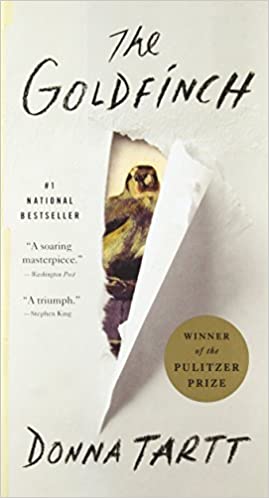

The Goldfinch

Cultural gatekeeping and Donna Tartt's dazzling 2013 novel

I read Donna Tartt's brilliant 2013 novel The Goldfinch 6 years late and was mesmerized. The immediate impression I had was one of pleasure, the deep satisfaction of witnessing another human being achieve mastery in their craft. As a lifelong football fan, I viscerally felt this description of another slate of 4 PM kickoffs winding down:

On game day, until five o’clock or so, the white desert light held off the essential Sunday gloom—autumn sinking into winter, loneliness of October dusk with school the next day—but there was always a long still moment toward the end of those football afternoons where the mood of the crowd turned and everything grew desolate and uncertain, onscreen and off, the sheet-metal glare off the patio glass fading to gold and then gray, long shadows and night falling into desert stillness, a sadness I couldn’t shake off, a sense of silent people filing toward the stadium exits and cold rain falling in college towns back east.

Tartt is a gifted writer who spent 11 years on The Goldfinch and it shows.

Beyond the beautiful prose, the book is full of profound meditations on the relation of art and mortality; the experience of trauma, substance abuse, and ennui; the liminal state of participating in a social strata to which one can never be fully accepted; and how the love of the idea of a person can be impervious to their reality. And of course, Boris, the most gloriously original fictional character I've encountered in some time.

I was excited then to get online and read what others thought of it. I was aware - it was on the front material of my digital copy - that the book had won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize and so expected a cavalcade of praise. Instead I was dismayed by the critical firestorm that the book had engendered upon its release. The criticism of The Goldfinch wasn't so much about the novel itself as it was about what the critics perceived the novel was claiming to be. In their minds The Goldfinch presented itself as literature which they decided it was most decidedly not. That, in fact, by being widely read and acclaimed as such The Goldfinch was doing the entire idea of literature a grave disservice.

This sort of critique was exemplified by James Wood in the New Yorker. Wood did not like the book. He thought it's prose and themes childish (how this can be the case when one of the major threads of the novel is substance abuse and dependence is beyond me, but I digress), it's characters out of central casting from a fairy tale, and it's narrative too fantastic to be engaging. Worst of all for Wood, The Goldfinch claims to be something that it is decidedly not:

Tartt’s consoling message, blared in the book’s final pages, is that what will survive of us is great art, but this seems an anxious compensation, as if Tartt were unconsciously acknowledging that the 2013 “Goldfinch” may not survive the way the 1654 “Goldfinch” has.

This is not a criticism of the book on its merits. It is a criticism of what Woods perceives to be the authors intent. The book is not only bad, it is especially bad because Wood claims that Tartt intends it as literature.

There are two levels on which this bothers me. First, it implies that trying and failing to create literature is somehow worthy of special disapproval. That the mere thought of attaining greatness opens one up for exceptional criticism. Second, it further implies the existence of a sanctified group of people with unique ability to judge whether a book is great or merely tries to be great. People like James Wood.

Why would a critic, who one assumes loves literature, seek to discourage people from attempting to write literature? Why is a book especially bad because it attempts and fails to be great? If anything such an attempt should be recognized and bemoaned as a misfortune, a writer as obviously talented as Tartt encouraged to try again. It's almost as if some critics are more jealous of their prerogative then they are devoted to their canon. But that would be judging critics on our perceptions of their intent, and that would be unfair wouldn't it?

Fortunately for you, dear reader, Wood is wrong on the merits of Tartt's novel. The Goldfinch is a brilliant book and you should read it.